Submitted by Robert P. Ellis

Northborough – The article by Alexandra Molnar, “Historic signs recognize Northborough’s industrial past along Assabet River,” in your Dec. 8 issue calls attention to a number of such industries, but its short account of industry in the building close to the Assabet Falls near Allen Street does not mention a once-significant industry, Gothic Craft.

Northborough – The article by Alexandra Molnar, “Historic signs recognize Northborough’s industrial past along Assabet River,” in your Dec. 8 issue calls attention to a number of such industries, but its short account of industry in the building close to the Assabet Falls near Allen Street does not mention a once-significant industry, Gothic Craft.

Twenty years ago, the Northborough Historical Society received a letter from the office manager of London Church Furniture, Inc. of London, Kentucky. “At one time,” he told us, “our company was owned by Gothic Craft.” To his question of whether Gothic Craft was still in business I had to reply negatively, because this Northborough industry, which had turned out fine church furniture for 35 years, had gone out of business in 1969. Although some of us can remember this industry, it has been largely forgotten.

The founder of Gothic Craft, Richard A. Butler of Revere, studied architectural design at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and later learned to design altars, baptismal fonts, pulpits, lecterns, pews and statuettes at a firm in Boston. When he decided to establish his own business, he claimed that “of all the places I looked at in New England, the Northboro setting was one of the choicest.” Butler chose to live as close to the Assabet as it is possible to get: in the section of the old mill building at the corner of Hudson and Allen streets that extends over the river.

According to a 1950 article in the Worcester Sunday Telegram, Butler was employing 35 to 40 skilled craftspersons. A decade later the force had grown to 50. They came from a wide variety of places. One of the best carvers came from Baden, Germany, in the Black Forest area famous for its vast stretches of oak trees.

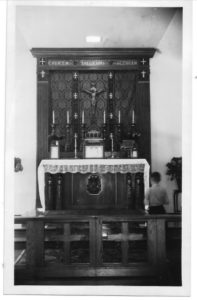

The favorite wood for church furniture, Butler said, was oak, which the author of the 1950 article aptly called “an invigorating resistance to their tools,” because it permitted the creation of complicated tracery, tiny pinnacles, niches, reversed curves and foliated cusping characteristic of the Gothic style. Butler purchased wood from oaks grown in the Appalachian mountains of West Virginia and Kentucky, ideal for his purpose because “the nature of the soil there makes for slow growth and forms the grain closer together.” When the slabs arrived, they were placed in kilns for a period from two to six months to reduce the moisture content to 5 percent, which would suit the church buildings that would receive the finished articles. Every job done at Gothic Craft, Butler maintained, was “an individual piece of work.”

The traditional furnishings of Catholic churches often called for Gothic detail, and church officials often accepted Burton’s designs. Gothic Craft fashioned an oaken throne for St. Paul’s Cathedral in Worcester, many furnishings of the Assumption College Chapel, and the entire interior of St. Joan of Arc in Worcester. But the company’s furnishings also graced Protestant, Eastern Orthodox and Jewish structures near and far.

By 1968 the direction had passed to Margaret E. Downey. She claimed that the recent Vatican II Council earlier in the decade had sought new church furnishings and thus provided much work for the company. Catholic worship, however, was becoming simpler and less ornate, and one wonders whether that council’s encouragement of a moderate use of images was actually running counter to the intricacies of traditional Gothic and damaging the prospects of craftspersons skilled in elaborate Gothic design.

At any rate, less than a year later, Gothic Craft went abruptly out of business. It is difficult to enumerate all the factors that may have led to the downfall. Perhaps the cost of importing wood from places as distant as Kentucky had also become a problem. Today London Church Furniture remains in business in a heavily forested section of Kentucky. A look at the design of its furniture in the company’s website, however, suggests that the Gothic element is largely gone. The styles of building and design and of life itself today offer fewer opportunities for the type of work exercised at Gothic Craft.

After Gothic Craft departed, the building became a part of a well-known New England store, Basketville, and some of the company’s products were manufactured there, but now the mill has become and will undoubtedly remain a “Residence at the Falls.”