HUDSON – July 4, 1894, started as just another Independence Day in the town of Hudson.

Residents were enjoying the holiday at Trotting (now Riverside) Park.

But, by day’s end, the town had suffered what is perhaps the greatest disaster in its history.

Blaze began during holiday celebration

At around 3 p.m. some boys were lighting off firecrackers at a small building near the F.H. Chamberlin shoe factory, which bordered the Assabet River mill pond. A fire started, and, helped by a strong breeze, it soon grew, spreading east through the downtown area, which contained many wood-framed buildings.

With people gathered at the park for the day’s festivities, including many of the town’s firefighters, the fire was able to get established before the fire department could turn out and begin fighting it.

The town’s telegraph operators sent word to neighboring towns seeking help fighting the blaze.

The city of Boston even sent firefighting equipment on a railroad flatcar.

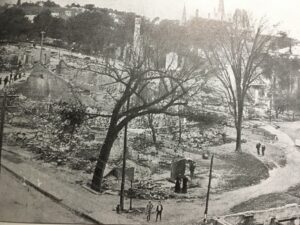

But, despite the efforts of the numerous firefighters, nearly 40 buildings spread over five acres had been destroyed within three hours of the conflagration. The property loss totaled roughly $500,000 dollars, the equivalent of $16 million today.

Struggling to contain the fire

Those fighting this blaze had to demolish several buildings with dynamite to create a fire break, Hudson Historical Society historian David Bonazzoli recently told the Community Advocate.

“They would have lost the entire downtown otherwise,” he said.

At one point, the fire burned through a hose stretched across the streets.

“You can’t fight a fire without water,” Bonazzoli said.

Tragically, there was at least one lost opportunity to respond sooner than the fire department did. Crews were putting in streetcar lines when the fire started, Bonazzoli said. One worker near the Lewis block downtown saw smoke. But his supervisor told him to ignore it.

“No early alarm went out,” Bonazzoli said. “If it had, they probably wouldn’t have lost as many buildings.”

The fire was big enough news to warrant a story in The New York Times the next day. That story bore the ominous headline “The Dangerous Firecracker” and listed all of the buildings lost, which included factories, tenements and a boarding house, and store blocks. Displaced businesses included the YMCA, the post office, several doctors, The Enterprise newspaper and a billiard hall.

The story concluded with a summary of the scope of the endeavor to bring the blaze under control.

“The high school building and Town Hall were opened for the reception of goods saved,” the story read. “Help was requested from surrounding towns, and engines came from Fitchburg, Clinton, Boston, Waltham, and Worcester, and a hose carriage from Maynard. The Boston and Maine Station building and others were on fire and saved only by determined efforts.”

Rising from the ashes

Hudson rebounded quickly from the tragedy, which luckily did not result in any loss of life.

Insurance covered about 80 percent of the rebuilding costs, and, within a year, all of the buildings had been replaced.

Some good did rise from the ashes.

“The town was built as needed during early industrial times,” said Lewis Halprin, author of two books about Hudson’s history that were published in conjunction with the Historical Society. “It was centered around the dam at the Assabet River. The fire destroyed that whole area. Restrictions were put in place that the new buildings couldn’t be built of wood. It provided uniformity to the town.”

The current brick and stone architecture of the buildings that replaced those destroyed by the fire is a major asset to Hudson’s downtown, Halprin believes.

“Architecture and economics go together,” he said.

Yet the fire’s losses extended beyond the buildings themselves and included some irreplaceable contents.

“R.B. Lewis was one of the main photographers of the town,” said Bonazzoli. “He lost all his negatives, and he had many historic photos of the town.”

The attempt by Lewis to get his large trove of photographic negatives away from the fire’s path was unsuccessful due to what Bonazzoli characterized as short-sightedness on another citizen’s part.

“Lewis offered a man who was using a wheelbarrow to move furniture $5, then $10, up to $20 to use it, but the man refused. So, some old furniture was saved but all the photos were lost,” Halprin said.

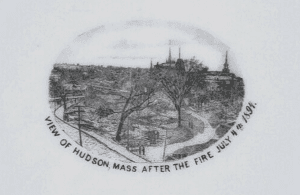

One of the interesting vestiges of the fire are the commemorative items that were produced.

China cups and dishes featuring a drawing of the fire’s aftermath were made in Germany for the Solon Wood Company.

Hudson’s main general store at the time, the Solon Wood Company was destroyed by the fire before being rebuilt and reopened, bigger than ever.

Its sale of an item that documented such a traumatic event is perhaps the ultimate symbol of triumph over tragedy.

RELATED CONTENT

Westborough office building has been an iconic presence for more than 50 years

Trail through Marlborough and Hudson was once part of the robust Fitchburg Railroad

Marlborough and Hudson’s Civil War sacrifices were substantial